The Original "You Gotta Believe" Team: The 1914 Miracle Braves

Blog post description.

12/9/20254 min read

The Original "You Gotta Believe" Team: The 1914 Miracle Braves

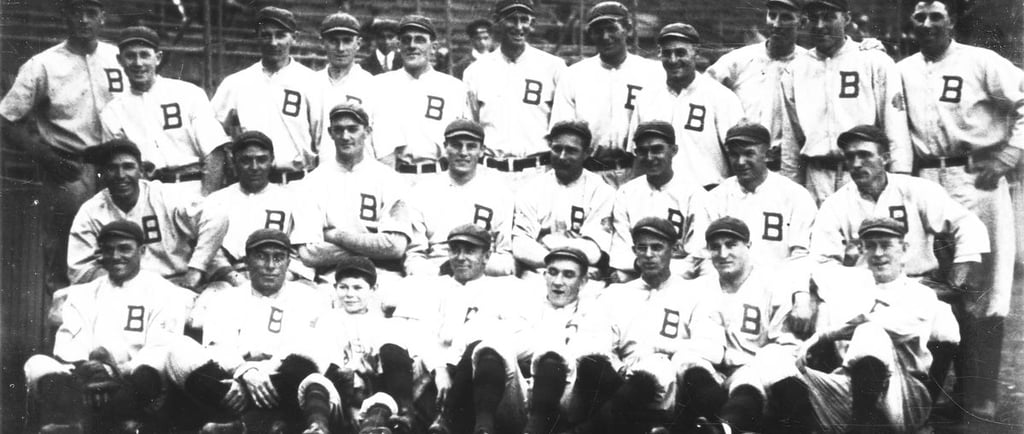

Every once in a great while, a team seemingly comes from nowhere, catches fire and ascends to the top of Major League Baseball. It's as if the ballplayers were hit by a bolt of energized lightning, in predestined alignment with the stars or touched by a magic wand from the baseball gods of luck. Such was the case with the 1914 Boston Braves.

The Braves had languished in the cellar for a decade, averaging 100 losses a year under seven different managers, four different owners, and with three different nicknames (the "Beaneaters," the "Doves" and the "Rustlers"). While other teams in the National League stayed relatively competitive and moved into steel-and-concrete stadiums, the Braves played their dreadful brand of ball in a rickety wooden ballpark, the South Ends Ground, with 5,800 seats—most of them rarely occupied.

In 1912 the franchise was purchased by former star pitcher John Montgomery Ward and two former high-ranking New York policemen who were known for their pay for protection skills, James Gaffney and John Carroll. Under their leadership, the team didn’t make any immediate improvement on the field, but at least they gave the team a new name that held the test of time, the "Braves."

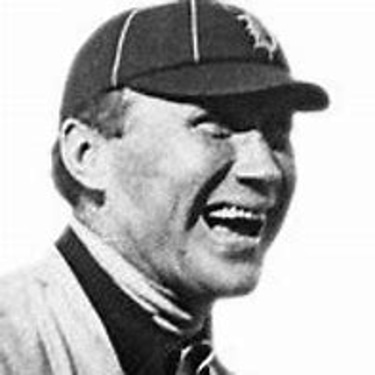

In 1913, the Braves named George Stallings as their manager, who like Connie Mack wore a suit in the dugout. Stallings was an old-style figure who it was said fancied himself as a cotton plantation owner from Georgia. Stallings also had a legendary temper. He would go into an uncontrolled rage over something as minor as a dropped fly ball.

But Stallings had an even worse trait when it came to his reliance on superstition. He hated yellow signs and yellow clothing. Yellow ballpark advertisements had to be painted over before he’d let the team play. He would freeze in position and tightly contract his muscles when his team started a rally. Once, his body constricted so much that he had to be carried off the field on a stretcher and taken to a chiropractor.

But George Stallings knew baseball.

In 1913, Stallings’ first season, he managed the Braves to a lackluster 69 wins and 82 losses but the wheels had begun to turn in his mind on how the team might reverse fortunes. By the start of 1914, Stallings had a lineup that he thought was tough enough to compete. Stallings told his players “Do what you want but don’t end up in jail and come to play every day.” They did exactly what they wanted. Shortstop Rabbilt Maranville once dove into a hotel fountain after a few cocktails and emerged with a goldfish between his teeth. Yet the very next day, Maranville let himself get hit in the head by a fastball so he could force in the winning run.

One of Stallings’ best moves was to convince ownership to buy the contract of legendary Chicago Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers before the season began. Stallings then released a few non-performing veterans and promoted five rookies to the roster who had never played a game in the majors. The Braves lost their Opening Day game to Brooklyn, then lost more games. Maranville came down with tonsillitis and Evers got sick. Yes, the Braves were losing but many of their losses were close, most only by one or two runs. Though even so, before long the Braves were deep in the cellar, 15-1/2 games behind the first place New York Giants.

The bottom was seemingly reached on July 18 when the Braves lost to a minor league Buffalo team during an exhibition game.

Then suddenly with little warning, the Braves got hot then red hot. They won 12 of the next 16 games on the road and rocketed to fourth place. The light hitting team began to get timely hits, especially from a relatively obscure left fielder, Joey Connolly. Maranville not known for his power, hit a clutch home run in one game to turn defeat into a victory. But best of all was the Braves' defense especially in the infield. Along with Maranville and Evers and first baseman Charlie “Butcher Boy” Schmidt, the team turned more double plays than the famed Cubs’ Tinkers-to-Evers-to-Chance squad.

The pitching solidified. From July 9, pitcher Bill James had a record of 19-1 with a 1.51 ERA. The only game he lost was 3-2 to the Pirates in 12 innings. Pitcher Dick Rudolph a curveball-spitball pitcher, went 26-10. Lefty Tyler, who had an unconventional windup motion, rounded out the big three pitchers with a 16-13 record. Even George Davis, a rarely used starter, pitched the National League’s only no-hitter that year in September against the Phillies.

As the team started to climb the standings, the city of Boston got caught up in Braves' fever. The Red Sox offered the Braves the use of Fenway Park. On their first home game at Fenway the attendance was 20,000. Among the fans in the stands was tavern keeper Michael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevey. He was the unofficial head of a small army of sports fanatics dubbed the Royal Rooters who happily transferred their loyalty from the Red Sox. By the way, Nuf Ced got his nickname by pounding his fist on the bar and exclaiming “Nuff Said” when he’d won a sports argument.

From July 19 to the end of the season, the Braves won an incredible 51 of 67 games. On Sept. 29, they clinched the National League pennant. The team was expected to lose the World Series to the dominant Philadelphia Athletics, who had a Hall of Fame pitching staff and a $100,000 infield. The A’s ace, Chief Bender, called the Braves “bush league.”

The Royal Rooters followed the team to Philadelphia for the first two games. Boston Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, his daughter Rose and her new husband Joe Kennedy (father-to-be of U.S. President John Kennedy) went along.

The Braves took the first game, shocking the Athletics with a 7-1 victory. They won the second game, too, 1-0. Upon returning to Boston, the Royal Rooters paraded onto the field before the game start in Indian costumes. They sang their fight song “Tessie” throughout the game which upset and unnerved the A’s pitchers. Braves catcher Hank Gowdy won the game with a 12th inning walk-off homerun, the only ball that left the park in the Series.

The Braves 3-1 victory over the A’s in the fourth and final game of the series inspired a raucous city-wide celebration. The losing manager, Connie Mack, was gracious in defeat. “A great team,” he said. “One of the greatest. It had great spirit and just wouldn’t be beaten.”

The Braves last-to-first rally still stands as one of the greatest reversals in baseball history. It was indeed a baseball miracle for the ages.