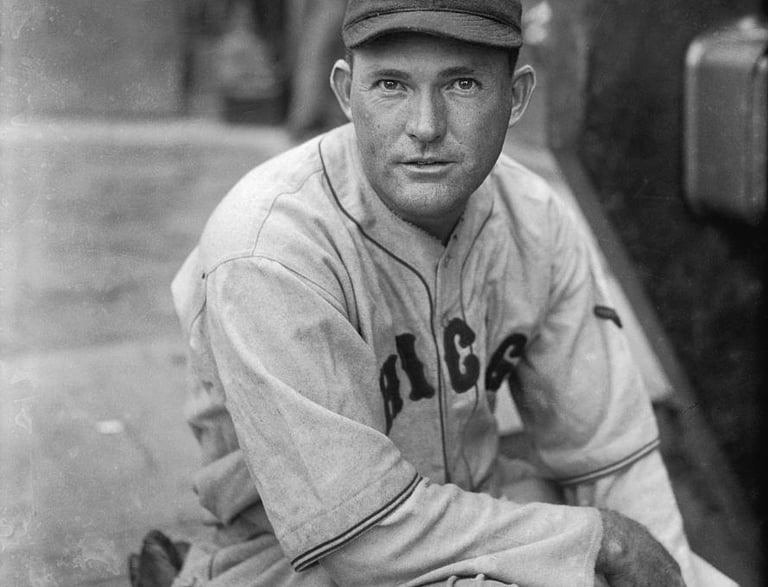

Rogers Hornsby: Cancer In The Clubhouse

Blog post description.

12/10/20254 min read

Rogers Hornsby: Cancer In The Clubhouse

For whatever reason, usually one connected with a flaw in personality, certain baseball players can cause havoc on a team. Some players are so toxic in their interactions with others that they drive down the morale of a team and actually affect its record adversely. Even the greatest of baseball players have caused negative impact. Rogers Hornsby who had an incredible .358 lifetime batting average over a Hall of Fame career that spanned 23 years was one such malcontent.

Perhaps because of his difficult and poor childhood in Texas in which he lost his father at age two, Hornsby never seemed to want to get close to anyone. Even worse, he was extremely cocky as he thought of himself as one against the world. This attitude led him to fight fiercely mostly for his own personal gains rather than team accomplishments.

Hornsby was a loner by nature who shunned after hours interaction with teammates. Much of this had to do with his own training regimen as he did not drink nor would he ever go to the movies. He reasoned both of these activities could impact his hitting ability especially his near perfect eyesight. Hornsby had other peculiarities. He ate ice cream every night before bed and always slept at least 12 hours. When on the road, Hornsby mostly sat in the hotel lobby and watched people until it was time to report to the ballpark. He also constantly gambled on the horses and over the years lost thousands of dollars.

Hornsby rarely talked about anything except baseball and horse racing. He usually roomed by himself on the road, and often showered and exited the clubhouse after a game without saying a word to anyone.

In 1918, Jack Hendricks became the St. Louis Cardinals manager. Hornsby despised Hendricks for unknown reasons and often second-guessed the manager’s game decisions outwardly in the press. It is even alleged that Hornsby let his batting average slide on purpose and at one point refused to play. Toward the end of the season, Hornsby publicly stated that Hendricks was a “boob” and his teammates were “stool pigeons.” Predictably Hendricks was fired soon thereafter.

Some baseball historians believe that Hornsby was easily frustrated by other ballplayers whom he believed to be less talented than himself. In a game in 1919, Hornsby failed to slide in a close play at home plate to which he responded: “I’m too good a ballplayer to be sliding for a last place team.”

Hornsby rarely argued with umpires as he correctly reasoned that this could influence their judgment against him on close pitches. However, he had no diplomacy in expressing any critical thoughts about others even in their presence. One New York sports writer recalled a story in 1927 when he ran across Hornsby eating in a restaurant with fellow team mate, Eddie “Doc” Farrell, a young shortstop. The writer asked Hornsby if the Giants could win the pennant to which he responded “….not with Farrell at shortstop.” This is probably why Hornsby mostly ate by himself.

In 1931, Hornsby was named player-manager of the Chicago Cubs replacing Joe McCarthy who teammates alleged he had secretly undermined. Most vocal against Hornsby were Gabby Hartnett and Charlie Grimm but the chorus grew to include other stars such as Hack Wilson, Kiki Cuyler and Billy Herman. Woody English told the press that he heard a firecracker in the stands and thought it was a gunshot aimed at Hornsby.

Cubs President William Veeck, Sr., who was not consulted with the Hornsby hire even resigned though he was wooed back by team owner, William Wrigley, with the promise that he would never be interfered with again. Veeck tolerated Hornsby until August of 1932 when he was fired with the Cubs back five games from first place.

Evidently, the team was so relived with Charlie Grimm as their new manager that they eventually won the National League pennant by four games. Subsequently, the players voted Hornsby out of any World Series compensation.

Hornsby’s personal life was often in shambles as well. In 1949 after the death of his son, Rogers Hornsby, Jr., an Air Force pilot whose B-29 crashed in a training exercise, Hornsby’s first wife refused to allow him access to the funeral.

Hornsby’s other son, Bill, from a second failed marriage, who had little contact with his father played briefly in the minors. Upon hearing that Bill had only hit .206 in 69 games and was released from Oklahoma City, Hornsby commented: “…Glad Billy learned early that he wasn’t a real player. Imagine how I would have felt, seeing the Hornsby name that low in the batting averages.”

In 1952 long after his playing career had ended, Hornsby was back in the Majors managing the St. Louis Browns. He had been hired by Bill Veeck, Jr., the son of Sr. who had fired him previously in Chicago. Hornsby only lasted 51 games before he was fired this time, but during the stint, he managed to get into a fight with legendary pitcher Satchell Paige and others on the pitching staff. The bad feelings stemmed from the fact that Hornsby had a habit of pulling pitchers by waiving his hand from the dugout.

When Hornsby was canned, the thankful Browns’ players presented Veeck with a ceremonial trophy that was inscribed: “To Bill Veeck, for the greatest play since the Emancipation Proclamation.” Pitcher Gene Bearden told the press: “They ought to declare a national holiday in St. Louis.”

Shortly, before his death due to a stoke, Hornsby was supposed to meet with Roger Maris for a presentation event which unfortunately Maris had to cancel at the last minute. Not to be upstaged, Hornsby simply quipped (about Maris): “The man couldn’t carry my bat.” Enough said.