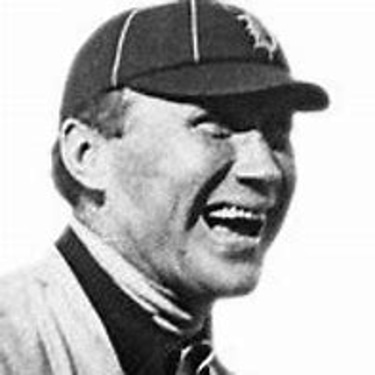

John McGraw, Charlie Grant & The Color Barrier

Blog post description.

12/10/20254 min read

John McGraw, Charlie Grant & The Color Barrier

In the early days there existed (as we all know) a strict sad discriminatory color ban on black athletes in Major League Baseball. If you were black, no matter how talented or deserving, there was no place on any all-white team. Your only chance for a career in baseball was the less financially rewarding and less glamorous black or Cuban leagues.

In March of 1901, Charlie Grant was working as a bellhop at the Eastman Hotel in Hot Springs, Arkansas. This evidently was Grant’s off-season employment as he was the starting second baseman for the black Columbia Giants of Chicago.

By chance, the Eastman Hotel was also the spring training headquarters for the Baltimore Orioles of the new American League. Rookie manager and future Hall of Famer, John McGraw, was tipped off by his own players about Grant as they had seen him dominate a pick-up baseball game of fellow hotel workers. Another version of the story suggests that a friend of Grant’s and a fellow black ballplayer by the name of Dave Wyatt connected Grant to McGraw. It is also certain that Grant knew two of the Baltimore players personally, Mike Donlin and Roger Bresnahan, as they had all grown up together in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Whatever account is correct, McGraw agreed to put Grant through some drills with the Baltimore squad. Almost immediately, McGraw recognized the finished talent that Grant possessed especially his quick reaction to ground balls and his breakout speed on the basepaths.

Although, McGraw had many vices and peculiarities, he was not an avowed racist like so many other white managers and front office baseball personnel of the time. McGraw saw Grant simply as a talent that he could use on the Orioles to give the team a competitive edge. Moreover, McGraw was desperate for a second baseman as his only roster player for the position was Heinie Reitz who was 34 years old and had been out of baseball for over a year.

Charlie Grant was light-skinned for a black man and he possessed relatively straight hair and high cheekbones. His features gave McGraw the idea to disguise Grant as a Cherokee Indian. To complete the ruse, McGraw anointed him with the name of “Charlie Tokohama” as “Tokohama” was the name of a river on a large antique map that hung in the Eastman hotel lobby. To further embellish the story, Grant was told to say that his father was white and his mother was Cherokee and living in Lawrence, Kansas.

McGraw even enlisted newspaper friends to publish various articles on Grant to give his background validity in which they describe him as a “...full-blooded Cherokee redskin wonder who will make an extraordinary presence at second base.” Another more prominent article on the signing of Grant appeared in the Washington Post on March 15.

Unfortunately, for Grant the first game of the season for Baltimore was scheduled for where else but Chicago, the same city where Grant had played for the Columbia Giants. Someone evidently tipped off Grant’s friends and fans as when the train arrived, several African Americans presented Grant with a ceremonial Welcome Back wreath and an expensive "real" alligator traveling bag. Grant, himself, did not attempt to hide his previous association to the team and posed for photographs with the well-wishers.

Predictably, it did not take long for the news of the event to reach Charles Comiskey, owner of the White Sox, who immediately objected. True to his racist form, Comiskey commented: “If McGraw keeps this Indian, I’ll put a Chinaman on third base.” Moreover, other American League owners, especially Clark Griffith evidently had incriminating inside information as well. Ban Johnson, American League President, who himself resided in Chicago was telegraphed to investigate and a counter story that suggested a plot to breach the color barrier soon appeared in the Chicago Tribune.

Perhaps, because it was McGraw’s inaugural season in the League and perhaps because he began to think that the controversy might lead to his suspension, the idea of including Grant on the Baltimore roster began to seem like a bad idea. He reasoned that the negative publicity wasn’t worth the trouble and Grant never played one game for the Orioles.

Grant resumed his career with the Columbia Giants and the team was crowned black league champions. In 1902, he then joined the upstart Philadelphia Giants, another top black team of the era. The following year he appeared on the Cuban X-Giants and participated in the first official black playoffs versus the Philadelphia Giants. Between September 12 and 26, the clubs met seven time with the Cuban X-Giants winning five games.

In 1904, Grant ended up on those same Philadelphia Giants and with his help the team soared to a 95-46-6 record. It is interesting to note that heavyweight champion Jack Johnson played for the team at times at first base. The championship series was again between the Philadelphia Giants and the Cuban X-Giants though Philadelphia ended up victorious this time. Grant played with various other black teams until he retired in 1916.

Unfortunately, his playing time pre-dated the official start of the Golden Age of Black Baseball also known as the Negro Leagues which technically began around 1920. His statistics and contribution to black baseball remain mostly unknown with the exception of his involvement in the John McGraw incident.

Grant subsequently moved back to Cincinnati and he had a career as a messenger for Western Union. On July 9, 1932, while sitting and relaxing on the sidewalk outside his apartment, he was struck and killed by a driver whose car blew a tire and jumped the curb.

Regrettably, baseball’s color ban would last until 1947 when Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson.